|

Biography

1950

born in Nauheim, Germany

1975-79

Hochschule für Bildende Kuenste, Frankfurt/Main, Germany

1979-81

Hochschule für Bildende Kuenste, Duesseldorf, bei Prof. Klaus Rinke

1978-81

Scholarship of the Deutschen Studienstiftung

1985

Founding of the "Gruppe Formalhaut", with Gabriela Seifert und Goetz Stoeckmann

1992-93

Guest-Professor at the TU Graz (with "Formalhaut"), Austria

1994

Price-winner für Baukunst, Akademie der Künste Berlin (with "Formalhaut")

1997

art multiple-Price, Internationaler Kunstmarkt in Düsseldorf, Germany

1998

Wilhelm-Loth-Price, Darmstadt, Germany

1999

Professor and President of Akademie der Kuenste, Nuernberg, Germany

2002 Intermedien Award ZKM Karlsruhe, Germany

2005 President of the Akademie der Bildenden Kuenste, Nuernberg, Germany

lives and works in Frankfurt/Main und Wertheim, Germany

|

Exhibitions since 1980 (selection)

Gallery

ak, Frankfurt, Oberflächen, Germany

Het

Apollohuis, Eindhoven, Blinker, Netherland

Gallery ak, Frankfurt, Plastik, Germany

Provinciaal Museum, Hasselt/Belgium

Storefront

for Art & Architecture, New York (with "Formalhaut")

Gallery Transit, Leuven/Belgium, Nature Morte

Lindinger + Schmid, Regensburg, Germany

Familientreffen, Stadtraum Rüsselsheim, Germany

Lenbachhaus

Kunstforum, München, Eine Population, Germany

Fliegender Wechsel, Stadtraum Seligenstadt, Germany

Landesmuseum Oldenburg, Landschaft für Sprint, Germany

Kunstverein Ulm, Schmutziges Gelb, Germany

ACP Viviane Ehrli Gallery, Zürich, Monochrom für Enthusiasten

Städtische Galerie Ravensburg, Materialprüfung, Germany

Kunstverein Kirchzarten, Fingerübung, Germany

Wewerka Pavillon, Münster, Im Gordischen Stil, Germany

Welcome, Installation zu den Opernfestspielen in München, Germany

Kunstverein Würzburg, Germany

Forum Kunst Rottweil, Hydra, Germany

Neuer

Aschaffenburger Kunstverein, Aschaffenburg, Germany

"Das große Hasenstück", Nürnberg, Germany

artLAB,

'Wien, Austria

ARTBOX, Gallery für Editionen, Frankfurt, Germany

Die

Speisung der Fünftausend,

Projekt für das XI. Internationale Bodenseefestival

APC Gallery, Köln, Percuhion (with Bernd Vossmerbäumer)

"Richard Wagner für das 21. Jahrhundert", Bayreuth, Germany

"Eulen nach Athen", Athen, Greece

Arthur Rimbaud, Charleville-Mézières, France

Gallery

Erhard Witzel, Wiesbaden, Germany

I understand

my work as an organizational principle, defined by and through space.

My pieces always have amore or less political intention, that means that they tend to make

statements about society.

Art is not a matter of dividing the world into Good and Evil, but rather it is a case that

art ,as one part of society , is moulded and defined by the will to unsettle and to

disregard or broaden hitherto inflexible conventions.O. H. 1999 |

Organized anarchy

Welcome! Four thousand garden-dwarves dressed in black and

white stretch out their hands to the visitors and bid them welcome to the Munich Opera

Festival. Although they are only small, their appearance is appropriate, their

presentation imposing, their choreography overwhelming. The visitors to the festival feel

at home and smile back at the dwarves. Then, among the thousand-headed horde they discover

a couple of anarchic exceptions, brightly coloured figures obscenely raising their middle

fingers. A filthy gesture? A dwarves´ revolt? A happening by Ottmar Hörl!

As unexpected and perplexing the parade of the dwarves might be for

the visitors, it is an articulate expression of the artistic method of its innovator and

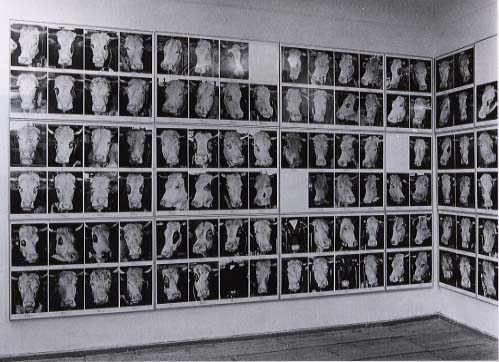

director – his "principle of organized anarchy" (Hörl 1982). Whether, as

in his ‘Kuhprojekt’ (Cow-Project, 1986), he clothed each of a small herd of cows

with a well-fitting cover of transparent polyester, or he had a uniformed police-marksman

fire two shots at the glazed front of the Historical Museum in Frankfurt (‘By the

way’, 1991), or whether he had a camera filming its own fall from a towerblock

including its inevitable destruction on hitting the ground – in all of Hörl`s works

one encounters the contradiction of chaos and order, he always lays bare the structural

elements of our material and social environment and thinks them through to their logical

conclusion until, to use Dürrenmatt´s words, events have taken the worst turn possible.

In this way he is able to undermine the ceremonial monotony of the festival opening, to

render apparent the natural parallel alignment of cows and the danger that art becomes

museumified and also the mechanical logic of the camera as man´s extended arm and

extended eye.

The integrity of the material

As a consequence of Hörl´s principle question about the secret

rules of order and the multiplicity of the forms of hidden structures his artistic work is

not confined to one specific form of expression or style. Thus conventionally defined

sculpture, happenings, photographic works and drawings all stand on an equal basis. They

are united by Hörl´s specific attitude to the material involved and by the special

attention he pays to those objects that interest him. This can be described as respect for

the integrity of things and living beings alike. It is of great importance to Hörl that

the sculptured form does not arise in conflict with the material but rather out of its

formal inherent qualities, according to the intention "to make the use of the

material in relationship to the desired results understandable".

The investigation of the world as it is brings with it a rejection

of sculptural forms that result from subjective arbitrariness, the respect for the

integrity of the material, a rejection of the traditional forms of sculpture, that take

their shapes from the forceful wrenching out of a form from wood or stone. In their place

Hörl has found that industrially produced plastic, initially for the most part corrugated

polyester, as the more appropriate and contemporary material, not only because of its

increasing presence in modern industrial society, but also due to its inherent aptitude

for serial production.

The principle of the series

The principle of the series, developed on the production lines of

the automobile industry and taken up by all aspects of the consumer industry and perfected

by the genetics and media industries, embodies a structural element of modern society.

Hörl takes this into account in that he integrates it as a constitutive moment in the

system of his sculptural concept. The sculpture ‘Zwilling’ from 1986 can be

regarded as a quantum leap in this process of perception. With its screwed together layers

of corrugated polyester Hörl, for the first time, doubles the form and in this way

underlines its structural repeatability and principle availability. For the same reason

the police marksman in Frankfurt had to fire two shots at the museum and not just one. It

was only in this way that the action became systematical and was liberated from the

character of an arbitrary deed and became apparent as a structural intervention.

The definition of the scope of a series is thus a factor not to be

neglected and is often an important conceptional element in Hörl´s work. Ottmar Hörl

takes great pains to always gain sight of the totality of a social manifestation. For

instance, if he reveals what it means, when there is talk every day of the threat faced by

numerous populations of the earth and to this end hee presents a complete picture of the

cow-population of the city of Passau at a specific moment of time (‘Eine

Population’), then he cannot be satisfied wiiith one facet, but has to present the

portraits of every one of the 943 cows living at this time in the municipal area of

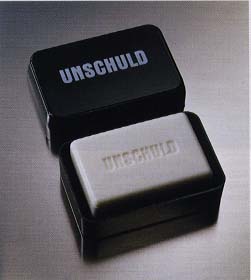

Passau. And also his extremely successful multiple ‘Unschuld’ (Innocence, 1997),

a bar of soap in a plastic box, achieves its particular virulence through the fact, that

the number made, 82 million, corresponds exactly to the population of germany.

Nature , Art, Society

Hörl´s interventions occur in the tense relationship between art,

nature and society. The dialectic of Art and Nature recognizable in his cow-projects, his

still-lives and his work with plastic plants is a representation of a thematic variation

of the higher question of the relationship of chaos and order. At first sight one might be

tempted to equate nature with chaos and art with order. This equation does not however

workout. Hörl shows this by making his broom-objects, symbols of the desire for order,

out of horsehair, while his proliferating green objects with grass, myrtle and ivy,

symbols of nature, are completely made of plastic.

Hörl’s social framework is most clearly apparent in his works

for public spaces. It is here that his idea of culture as a "link between a highly

developed technology and the completely ignored consciousness of mankind today" finds

its most effective place. For this reason Hörl pleads for a new seriousness in the

approach to art in public spaces: "Artists must learn to place their fingers on the

wounds of the public. That is not possible in isolated galleries and museums." Hörl

has shown just how this can be achieved in his numerous interventions in cities. Most

striking was his work ‘Street Gang’ (Aschaffenburg 1992), in which he installed

the complete range of 20 different rubbish containers according to the catalogue of their

manufacturer. The absurd grouping of the partly rustic and partly trendy containers not

only takes as its theme in an ironical manner the virulent rubbish problem of our cities,

nor is it solely an invitation to a functional and aesthetic comparison, above all it

undermines the certainty of salvation of a society that forever presents technological

solution to social questions. Just how far Hörl can be seen as an "offensive and

direct strategist of a new form of public art" is shown by a serial sculpture

‘Familientreffen’ (Family meeting, 1992) in and around the town of Rüsselsheim:

a multiple silhouette of the contemporary family developed from templates for

architectural drawings, which in its material (laquered steel), serial nature (industrial

production) and colour variety (multicultural workforce) reflects very precisely the

sociocultural situation of the car-producing city. And finally when Hörl , in one of his

latest works, plants a blue house at a precarious angle on a hill at the entrance to the

town of Ravensburg, then he marks by means of organized anarchy the sensitive transition

of the countryside to the town – a place which on account of the regular failings of

modern town planning is generally dominated by anarchic organization.

Sculpture as a principle of organization

In spite of their principle conception and in spite of the partially

rather strange appearance of the materials used, Hörl’s works are marked by a

pronounced aestheticism. By isolation and accumulation, arrangement and association,

progression and rhythmic presentation he succeeds in wringing new aesthetic qualities from

banally functional objects. When pipes are mutated to ‘Sculptures in Gordian

style’ (1998), this not only represents the ironic retroactive transformation of the

technological world into a mythical age, but also an ability to play with the beauty of

the bizarre. However much Hörl’s work deals with the questions of the confrontation

of natural and social reality, at the same time it always articulates the art-historical

and art immanent correlation. Thus aesthetics, irony and quotation, often to be found in

the titles, are essential aspects of his work. In conclusion, if one attempts to define

Hörl’s artistic strategy, then one can make use of the phrase he himself coined

"sculpture as a principle of organization". This encompasses two aspects: the

methods of the artist to order and structure objects of his choice according to their

physical and visual qualities in an experimental manner until they begin to shine and the

specific interest of the artist to trace the systems of social order, hidden as they are

in materials (ready-made plastic parts), tools (cameras, templates) and social functions

(opera festivals), and to think them through in the state of order to their conclusion and

thus provides at least an initial impulse to reflect upon their inherent sense.

Thomas Knubben (The author is the

Kulturreferent of Ravensburg and director of the Städtische Galerie Altes Theater.)

|

| |

|

|